It shouldn’t be terribly surprising that I have a Cascadian flag bumper sticker on my 90s Ford Ranger. That’s its natural environment. Cascadia is not a real political movement, it’s a rhetorical and aesthetic flourish – and a turn-of-the-millennium-flavored one, at that. It’s got Gen X vibes. It belongs between a COEXIST and a FREE TIBET. It’s the geopolitical version of threatening to move to Canada. [1] It’s giving Rock Against Bush.

For the non-locals in the audience, Cascadia is the name given to a proposed independent country in the Pacific Northwest. The idea is that the Cascadia bioregion – the interconnected ecosystemic zone of the coastal temperate rainforests and the Columbia and Fraser River watersheds – is also an area of shared human values and needs, and that a locally based polity would be more likely to treat the land with respect, develop in a way that respects the region’s carrying capacity, and deliver the kind of government that people want. It’s part of a larger bioregionalist philosophy that advocates structuring society and economics around these contiguous environmental zones.

The details vary depending on who’s talking. Some maps just depict Cascadia as consisting of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, the present-day political units at the core of the region. Others, more in the spirit of things, forego the artificial borders drawn by settlers and define the area by biomes and river networks. Cascadia has a flag – a blue, white, and green tricolor with a Douglas fir at the center – but that’s about all the “movement” really consists of. Unlike in Europe where every region has its own group of organized separatists with national anthems ready to go, there’s no micro-party agitating for an independent Cascadia; even the artist who designed the flag says it was about making a localist statement rather than promoting formal secession. Most people who talk about Free Cascadia are being hyperbolic. The flag is something to hoist at a soccer match or on the porch of your scruffy community house to signify a certain regional pride and a distaste for American nationalism.

But! It hasn’t always been thus. There is a genuine if spotty tradition of secessionist politics in the Pacific Northwest. The idea of a Free Cascadia has been taken seriously in the past. Speaking as a working bioregionalist whose demographic details have now made her an enemy and a target of the American state, this seems like it might be an appropriate time to take it seriously again.

Before colonization, this was one of the wealthiest and most cosmopolitan areas of the continent. Relative to the rest of indigenous North America, the worlds of the Chinookan cultures on the lower Columbia and the Salishan cultures further north were densely populated and crisscrossed by political and trading networks. These were based around sites for harvest, for hunting, and for netting the ubiquitous salmon. Sites of seasonal salmon harvest, like those at Celilo Falls near today’s The Dalles, brought together thousands of people from all over the region. [2] This was not a utopian world, but it was an integrated bioregion. That is, until the first white settlers came with survey stakes to divide everything into fungible land grants.

Even after the Anglo-American invasion began, though, there was no guarantee that the Cascadia region would be divvied up between the two empires. Popular historiography claims that Americans have always been one united people through thick and thin, with the Confederate secession as a nasty exception that proved the rule. Our politicians invoke unity as a value in and of itself, often as a means of coercing agreement to their most divisive, destructive, and discriminatory ideas. While it’s true that we don’t have any real secessionist movements in America today, the notion of eternal unity is mostly just propaganda, especially when it’s projected back to the first century of the United States. Independence based on regional interests and differing political values was advocated by trans-Appalachian settlers in the late 1700s, by New Englanders during the War of 1812, and by Northern abolitionists during the runup to the Civil War. [3] The Pacific Northwest was no exception to this trend.

In the early 1840s, the Oregon Country was theoretically under “joint occupation” by America and Britain, but that didn’t mean anything in practice. Neither country collected taxes, provided services, or really exercised any control there at all. The indigenous peoples were undergoing hideous demographic and societal collapse from epidemic diseases, not that the newcomers would have abided by their customs anyway. It was a total power vacuum. The settlers living in this contested zone were a mixed bunch – some were British subjects of Québecois or Metis origin, others were American homesteaders. Before long, this scattered community of rugged individualists started to run into the kind of problems that required a legal framework to deal with, and in a much-mythologized meeting at the hamlet of Champoeg they voted to create the Provisional Government of Oregon.

The biggest question was not what this government would do – at first it just ran probate courts and law enforcement – but what its longer-term purpose was. Most American-born settlers wanted annexation to their home country, but others were less sure. Proponents of independence were concerned by simple facts of economic and political isolation. The transcontinental railroad was still many years away, and it took months for news and trade goods to arrive by ship. Did it really make practical sense to join up with a country still concentrated on the East Coast? Wouldn’t retaining local self-government make more sense? [4] This wasn’t bioregionalism, obviously, but these people were asking some of the right questions.

The Provisional Government’s first gubernatorial election, in 1844, was a duel between the “American” and “independent” factions, the former represented by merchant George Abernethy and the latter by a one-eyed mountain man named Osborne Russell. Although Russell had been born in the United States, he’d spent his adult life as a fur trapper in politically contested frontier areas, and he was wary of American annexation. He and his supporters advocated for a permanent, independent government, free from both America and Britain: a “Pacific Republic.” They weren’t alone in this notion; back in the metropole the Pacific Republic idea was also endorsed by some leading Americans like Horace Greeley and Daniel Webster who thought that the distances involved were too great to manage. [5]

Specifics on the “independents” and their motives are hard to come by these days. After annexation and statehood, the current border situation seemed retrospectively inevitable, and most histories portray it as such. More recent scholarship, though, argues that we can see evidence of a strong independence movement through the venomous written attacks by its opponents. The reason we don’t have many people on the record as backing independence is that after annexation, they were afraid of being branded traitors to the United States. [6] I’d add to this the fact that Osborne Russell’s gubernatorial campaign got over a quarter of the vote, which is distinctly a minority but also distinctly not a crazy fringe minority. [7]

The Oregon Treaty ran an artificial border through the Cascadia bioregion in 1848. Everything above the 49th parallel north was British Canada and everything below was the United States. The material realities – the fact that the border was crossed daily by flowing water, migrating fish, drifting pollen, and herds of elk, or the fact that it cut right through the network of Salishan civilizations – no longer mattered to civil authority. With a few exceptional moments of comical confrontation (like the Pig War in 1859) the border has remained fixed ever since. But that hasn’t stopped some people recognizing how historically contingent it is and pushing against it.

The next attempt to change the border situation came on the eve of the Civil War. For some westerners with pre-existing beefs with the federal government, division back east would be an opportunity for the west coast to secede, too. Support for a Pacific Republic was more widespread in California, where it was a joint cause of Southern-born Anglos and of Californio ranchers who had been dispossessed after the Mexican-American War. In Oregon, most of the population backed the union – except in the Rogue Valley, which had been settled by Southerners and where Confederate sympathy was rife. (Not much has changed there, huh?)

Separatists in California plotted to seize the federal arsenals in San Francisco, while rumors swirled of similar cells up the coast, although none of it ever broke into open warfare. [8] (One paper dismissed the abortive Pacific Republic thus: “No one in Oregon thinks of such a thing, unless it is some brainless squirt of Democracy who is not able to pay his board bill.” [9]) Obviously, these racists’ plots are not a positive movement to emulate, but I mention them because they’re more proof that secessionism wasn’t always just hyperbole: the dissolution of the United States and the secession of Pacific states was once conceivable. The dissolution of Canada, which was not yet federated into a single colony, was also on the table in the 1860s. A substantial minority in British Columbia favored annexation into the United States because their economic ties to San Francisco were much tighter than those to the rest of the British colonies back east. Now that we are in the greatest existential crisis that America has faced since the Civil War – one that is increasingly drawing in our northern neighbor, too – there’s no reason any of this couldn’t become conceivable again.

As far as I can tell, after this era, Pacific secessionism disappeared as even a rhetorical idea for a century, and when it reemerged it was in a very different context. As a disillusioned post-1960s America began to ponder new forms of civic engagement and ecologically responsible living, people in the Northwest and Northern California appeared to be pointing the way. Oregon in particular was doing something entirely unprecedented. Throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, an active populace and a reforming state government collaborated to halt freeway construction and “urban renewal” projects, place the state’s beaches in the public domain, clean up pollution in the Willamette River, encourage artisan manufacturing, mandate recyclable beverage containers, experiment with new forms of cooperative life and labor, decriminalize cannabis, attempt carrying capacity restrictions on industrial development, and enact unprecedented comprehensive land-use planning. (Whew!) It was one of the only times and places in American history where society seriously confronted the contradiction inherent in the capitalist drive for infinite economic growth on a planet of finite resources. Once this political creativity was brought to bear on the 1973 energy crisis, Oregon’s success attracted nationwide attention and admiration. Governor Tom McCall went on a nationwide speaking tour touting the “Oregon Story,” and mused about running for president on a third-party platform to take his state’s values nationwide. This is when some of the contemporary stereotypes about the Northwest began to evolve.

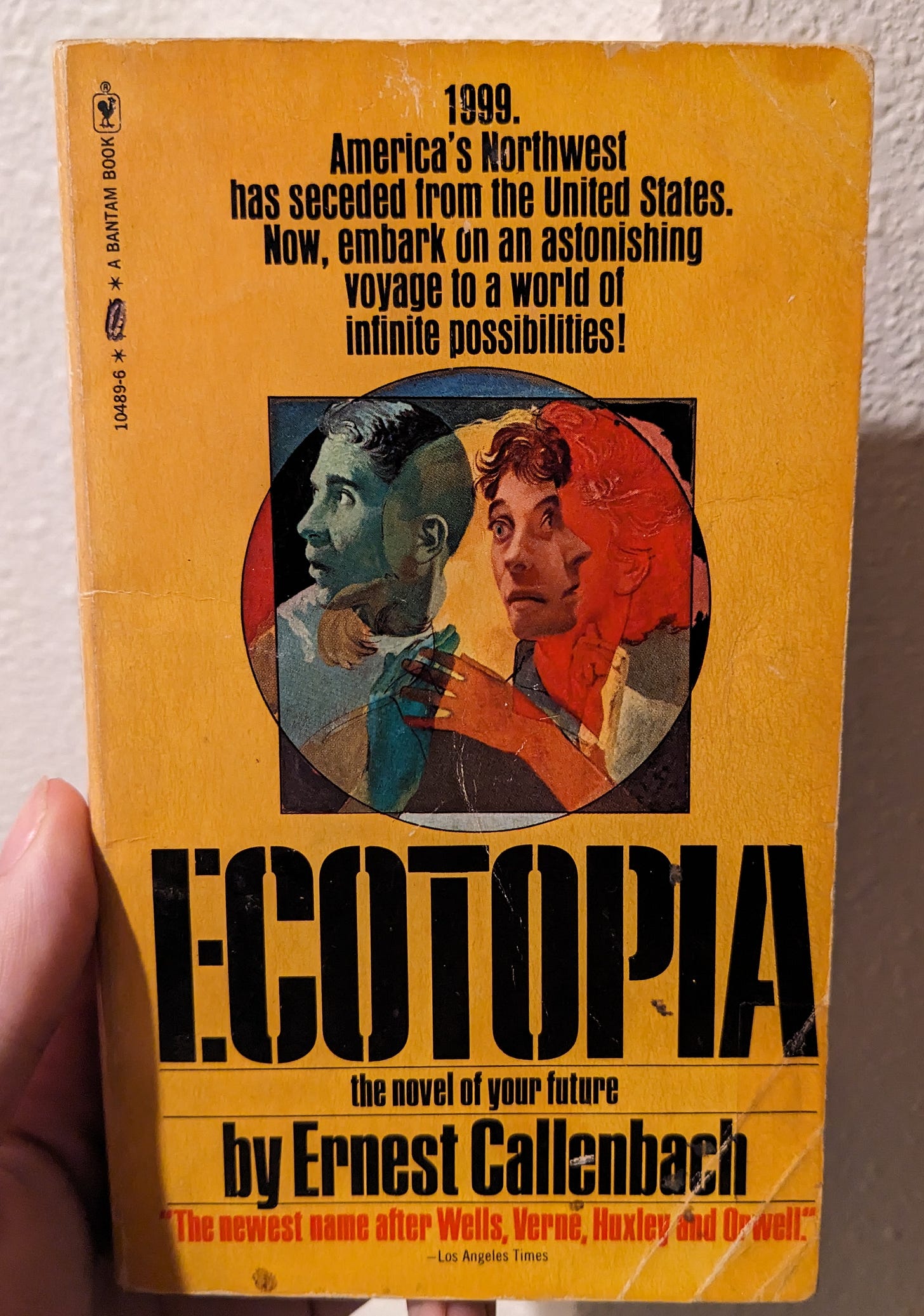

This idea of the region as an eco-political model to follow was taken to its secessionist conclusion in Ernest Callenbach’s 1975 book Ecotopia, which is as useful as a primary historical document as it is bad as a novel. In the distant future year of 1999, the Pacific Northwest has split from an economically decadent United States and is now a cloistered revolutionary state known as Ecotopia. A cynical American investigative reporter enters the new nation, observes its wise ways of steady-state economics and free love, and falls in love with his guide as his skepticism melts away. It’s Avatar or Disney’s Pocahontas but with hippies and it’s bound to invoke a certain degree of eye-rolling, but also a certain guilty pleasure, because as corny and Problematic as it is there still something compelling about the vision.

Around the same time Ecotopia came out, bioregionalism was being codified as a concept, and that’s the combination that birthed the contemporary Cascadia idea. While the bioregional model has inspired a lot of great scientific and regulatory work since then (the government program I work for is basically bioregional in nature) it still hasn’t become a real political movement in the way previous pushes for a Pacific Republic were.

Could it become one, though? The issue of estrangement from America’s and Canada’s centers of political and financial power, the same issue Osborne Russell and the “independents” were concerned about, hasn’t actually gone away. It’s just harder to see. Our forests are cut down and the logs shipped out of state to non-union mills, while our rivers are heated until the salmon die by the dams that power the tech industry’s data centers. A couple individuals here get rich but by and large any economic benefits go elsewhere. Over a quarter of Washington’s land and over half of Oregon’s is owned by federal bureaucracies that we have almost no control over – especially as residents of low-population, non-swing states who political candidates feel no need to pander to. It takes constant, Sisyphean political organizing to stop the feds from clearcutting the forests where we get our drinking water or letting nuclear waste leach into the Columbia. And forget about getting them to do prescribed burns! These are survival priorities for every life form here in Cascadia, and they need to worked on internationally across the region – but instead decisions are being made based on what will most appeal to the Republican Party base of retired car dealers in Florida.

This isn’t a manifesto, this is a history lesson, and I’m not going to claim that a Free Cascadia would be a utopia. The highest-level political structures in this region are all garbage in one way or another. Oregon’s ruling Democrats are lazy and corrupt, Washington has one of the most regressive tax codes in the country, and British Columbia’s supposedly leftist provincial government is plowing ahead with old-growth logging. Not everyone here is ecologically minded or socially liberal; Phil Knight and Jeff Bezos live in our bioregion and so do the Nazis of Coeur d’Alene and Clark County. By sheer demographics, an independent Cascadia would still be a settler-colonial state just like America and Canada, and I hardly have to remind most of my readers about the ugly history of anti-black racism here, from the Provisional Government’s exclusion law to the present-day brutality of our police departments.

The thing is, all of this shit is bound to be easier to fix on a smaller-scale, regional level. Our state governments are greedy for timber money – but they’re not taken over every four years by evangelical Republicans who believe that conservation doesn’t matter because the Rapture is around the corner. Our rural areas are full of scary right-wingers – but they’re not given massive electoral advantages by an unreformable eighteenth-century constitution. Our power grids have some negative externalities – but everything we try to do to make them better is interfered with by the feds, whether they’re trying to shut down wind farms or halt dam removal negotiations. While I won’t go too far into the details of my job, I see firsthand the way that doing environmental work on a local level consistently delivers better outcomes than massive, industry-captured national bureaucracies like the Forest Service can. And without the constant hateful drone of the American national media our urban-rural divide would almost certainly not have become as vicious. I sincerely doubt that an independent Cascadia would perfectly fit my personal queer low-tech eco-anarchist political vision, but it would be a much better place in which to fight for it.

Okay, that started to sound a little like a manifesto. What this article is really about, though, is how arbitrary national borders are, how they’ve been questioned in the past, and how malleable they can still be. Being part of the United States puts everything we care about in the hands of a political system we can barely affect, run by people who do not share our values. What if it was optional? Everything else about our constitutional setup is now in question, so why not put our borders on the table, too? What if we could move or abolish those violent lines to better reflect our needs – to live not as pledgers to the flag but as drinkers of Cascade mountain water?

Like the poem says: lines on a map are merely conventional signs.

If you liked this article (or if you didn’t, but liked the last two personal essay ones) consider a paid subscription. If I start bringing in money with my writing, I can devote more time to putting these out there for you!

[1] Although that’s not as much of a punchline as it used to be.

[2] There is an excellent if a little sociological-jargony description of the salmon harvests at Celilo in the first chapter of The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River by Richard White, but I’ve been meaning to read some actual indigenous writing on the topic – watch this space.

[3] For more on this idea, see Richard Kreitner, Break It Up: Secession, Division, and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union (Little, Brown, 2020).

[4] Thomas Richards, Jr., “‘Farewell to America’: The Expatriation Politics of Overland Migration, 1841–1846”, Pacific Historical Review 86, no. 1 (2017), 34-35.

[5] Kreitner, 206.

[6] Richards, 149.

[7] Charles Henry Carey, The History of Oregon (Pioneer Historical Publishing Company, 1922), 394

[8] Kreitner, 259.

[9] Robert W. Johannsen, Frontier Politics and the Sectional Conflict: The Pacific Northwest on the Eve of the Civil War (University of Washington Press, 1955), 187. By “Democracy” the writer meant the Democratic Party, which was the pro-slavery faction at the time.

Wow Opal this is incredibly impressive. Thank you so much for sharing this info and your thoughts—- you are an excellent writer.